How the piggyBac® Transposon Sheds Light on Breast Cancer Drug Resistance

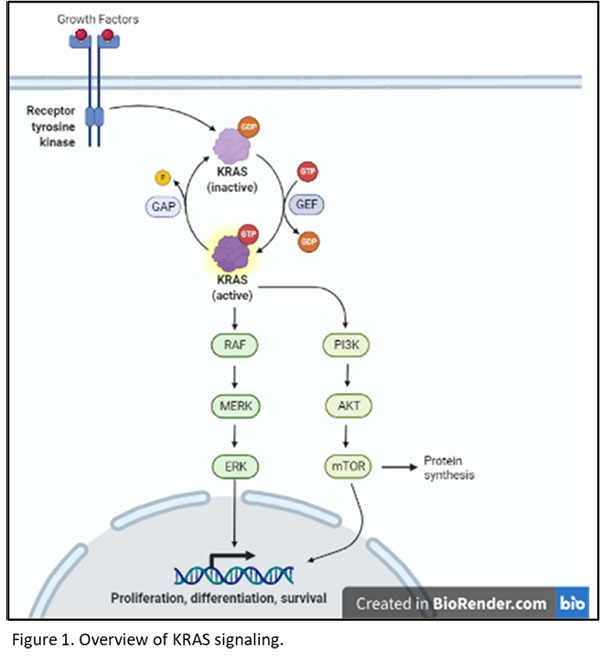

With over 2.2 million annual cases, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, but drug resistance remains a formidable challenge, particularly due to the development of drug resistance in recurrent or metastatic cases.1 The activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, driven by mutations in the PIK3CA gene, is a common oncogenic driver and plays a pivotal role in breast cancer development.2

Alpelisib, a PI3Kα-selective inhibitor, has shown promise in treating patients with PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer. However, studies have shown that certain mutations confer resistance to alpelisib, including upregulated retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and loss of phosphatase and tensin homologue protein (PTEN).3

Crucial Role of the piggyBac Transposon

In this context, a new study has harnessed the power of the piggyBac transposon system to unravel these key resistance mechanisms and propose a novel therapeutic strategy.

Auf der Maur and colleagues performed a genome-wide transposon-mediated mutagenesis screen using a mouse model of PIK3CAH1047R-driven mammary tumors.4 To do this, the team combined the piggyBac (PB) transposon system5 with a murine whey-acidic protein (WAP)-driven and PIK3CAH1047R mutant mammary tumor model.6

The piggyBac system allowed for the identification of NF1 loss, a negative regulator of RAS, as a resistance mechanism against PI3Kα inhibitors. The study further elucidated the metabolic changes associated with NF1 loss, revealing enhanced glycolysis and lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancer cells.

Figure 1. Illustration of the transgenic mouse lines used for the in vivo transposon mediated resistance screen.

By leveraging the piggyBac transposon system, this study has shed light on the mechanisms underlying resistance to PI3Kα inhibitors in breast cancer. The identification of NF1 loss as a resistance mechanism opens new avenues for more effective therapeutic strategies. As such, the group observed synergistic anti-tumor effects when NF1 knockout cells were treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) along with a PI3Kα inhibitor.

These findings also highlight the importance of utilizing innovative genetic tools like piggyBac to unravel resistance mechanisms and propel advancements in breast cancer treatment. This research offers hope for improved treatment strategies and underscores the power of the piggyBac system in advancing our understanding of drug resistance in breast cancer.

Learn More About piggyBac

The piggyBac system offers a versatile and efficient approach for genome editing, with applications across diverse research fields. Its remarkable cargo capacity of over 200kb sets it apart from other transposon and viral delivery vehicles, and makes it the ideal choice for creating stable cell lines.

To learn more about piggyBac and how Hera can help accelerate your gene editing research with our toolkit, click here.

References

- Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of Incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021; 71: 209-249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

- Miller T.W., Rexer B.N., Garrett J.T., Arteaga C.L. Mutations in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway: role in tumor progression and therapeutic implications in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011; 13: 224 https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3039

- André F., Ciruelos E., Rubovszky G., Campone M., Loibl S., Rugo H.S., Iwata H., Conte P., Mayer I.A., Kaufman B. et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA -mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019; 380: 1929-1940 https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1813904

- Auf der Maur, P., et al. (Year). N-acetylcysteine overcomes NF1 loss-driven resistance to PI3Kα inhibition in breast cancer. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(4), 101002.

- Rad R., Rad L., Wang W., Cadinanos J., Vassiliou G., Rice S., Campos L.S., Yusa K., Banerjee R., Li M.A. et al. PiggyBac transposon mutagenesis: a tool for cancer gene discovery in mice. Science. 2010; 330: 1104-110 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193004

- Meyer D.S., Brinkhaus H., Müller U., Müller M., Cardiff R.D., Bentires-Alj M. Luminal expression of PIK3CA mutant H1047R in the mammary gland induces heterogeneous tumors. Cancer Res. 2011; 71: 4344-4351 https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3827